By Sabrina Duda, Head of User Experience, VERJ | A LAB Group Agency

What makes us human?

Culture is what differentiates us from the other living creatures on earth. Culture can mean society, nationality, religion, language, also subcultures and slang. Culture defines who is an insider or an outsider.

Culture is inextricably linked with communication. We communicate via language, mimicry, body language cues, styling, clothes. Signs, symbols and icons also transfer meanings between people and objects or brands. In short, humans are constantly communicating, even if we’re not doing it verbally or consciously. If you’re tuned in, you will hear the message loud and clear.

Learning how to communicate with others is a social process regardless of the channel. Every channel of communication needs a language. Semiotics is the language of signs. These signs can be visual, auditory, tactile, or a combination of all three. We use signs to interact with each other: body language, mimicry, gestures, even sounds.

Meaning can be transferred in various ways:

- The Braille alphabet, which enables blind people to read and write, is a system of raised dots representing the letters of the alphabet.

- Morse code consists of dots and dashes, which can be transmitted as electric current, waves, light or sound, or any other methods available. SOS is signified by three dots, three dashes, three dots and is internationally recognised by the treaty. Morse code is still taught in the military.

- Church bells signify the time of the day by chiming the number of hours on the hour.

- We immediately understand the meaning of the sound of our alarm bell in the morning, even if we sometimes pretend we don’t.

- The beep of our car’s parking sensors signifies the distance to a nearby object.

Cultural codes

Cultural codes differ, depending on the culture. For example, the number four has negative associations in China as it’s associated with death.

But to make things even more complicated, cultural codes can also change. For example, contrary to modern-day expectations, in 1918 “The generally accepted rule is pink for the boys, and blue for the girls. The reason is that pink, being a more decided and stronger colour, is more suitable for the boy, while blue, which is more delicate and dainty, is prettier for the girl” according to Trade publication Earnshaw’s Infants’ Department. The popularity of blue sailor suits in the 20th century contributed to making blue the colour for boys instead of pink. Pink was first established as a female gender signifier in the 1940s.

Making signs understandable is a challenge within cultures, let alone across them. International airports are a perfect place to examine effectiveness. Airport Schiphol in Amsterdam is a famous example of excellent wayfinding and signs which are understood by all cultures. Wayfinding is crucial in 3D physical space, but also in digital worlds. Good information architecture is vital in helping users with wayfinding in the digital space. Signs guide us. It can be a simple arrow pointing in one direction or a more complex icon on a website.

Culture & brands

But of course, this also translates into the brand world. Brands use signs to show what makes them unique. When they don’t get it right and disregard their target audience’s culture, it has consequences. Studies have shown that semiotics may be used to make or break a brand. Culture codes strongly influence whether a population likes or dislikes a brand’s marketing, especially internationally. If the company is unaware of a culture’s codes, it runs the risk of failing in its marketing.

An interesting example of a global brand that struggled with this is Disney. With Disneyland Japan, it worked very well as the Japanese value ‘cuteness’, politeness and gift-giving highly in their cultural code, but the launch of Euro Disney in Paris came a cropper against underlying European cultural codes. Since being described as a “cultural Chernobyl”, the attraction has worked hard to overcome these cultural challenges and become Disneyland Paris – one of the foremost tourist attractions in Europe.

Humanising experiences

Being human means belonging to a certain culture, and we are humans because we have a culture. Semiotics analyse our culture and the meaning of signs and symbols within it.

Signs are used for wayfinding in the physical world; icons are used for wayfinding in the digital world. That’s why semiotics is so important for UX practitioners. We need to find signs with the matching cultural meaning to support users online and give them great experiences. Taking into account the cultural context of our users or customers is crucial to humanising experiences. We cannot create outstanding customer experiences without this research. We have to research the culture of our target users and customers to create signs they understand. When we do this, we signal to our customers. We tell them: “we know you, our brand is from the same tribe (culture) as you, you can trust us. When you use our brand, you will be part of our (desired) tribe”.

Humanising experiences means researching the cultural context, the signs and their meaning. What kind of experience do we have to create for users in a particular culture to make them feel their needs as human beings are met?

An interesting fact about lawyers is that older deeds are written without any punctuation because lawyers believed that the meaning lies in the sentence alone; any additional punctuation is therefore unnecessary. From a non-legal perspective, these deeds resemble a stream of consciousness, without any structure helping the reader extract meaning. The question here is, who is the target group for the deed, the lawyer or the client….

Experiences as stories

How do humans experience the world? The simple answer is: in stories. Look at human cognitive development, and you’ll find that children learn a language by remembering stories. We think in stories, and we remember in stories.

Storytelling is a means for sharing and interpreting experiences. Human knowledge is based on stories, and the human brain consists of the cognitive machinery necessary to understand, remember and tell stories. They also mirror human thought as we think in narrative structures and will most often remember facts in story form. Stories are universal in that they can bridge cultural, linguistic and age-related divides.

That’s why it is so important for a brand to tell a story in its branding and advertising strategy – to engage and be memorable.

In UX and software development, we also use the concept of storytelling in a way that’s not dissimilar to creative writing. We create user stories: As a user of that system, I want to do this activity so that I can achieve that goal. It is an informal, natural language description of features of a software system.

Personas & journey maps as stories

Personas and journey maps are crucial in UX as it allows us to create empathy and ensure user-centred development. A persona is essentially an actor in a story, which is described in a journey map. Contextual research in UX explores the setting and situation of the story: the context of use. The personas and journeys are then based on insights from user interviews and contextual research. They serve two different purposes – personas help us to emphasise with the customer and journey maps help to identify emotions, needs and opportunities.

Companies don’t always pay much attention to who their customers are, the culture and context they belong to, what is driving them, and not least – what they feel. Emotions are the driver behind human decision-making. Only in analysing behaviour and emotions within a cultural context can we find out why people behave, think and feel in a certain way. This knowledge is necessary for creating great experiences for them.

In contextual research, user researchers explore the context of a service or application. In which situation are users using this service? Who else are they interacting with?

This is especially important for more complex services or for B2B and work context.

Ethnographic research has traditionally explored other cultures in remote, exotic areas. But we don’t have to go that far. Take youth culture. Designing products for them – be it digital or physical – requires designers to immerse themselves in the youngsters’ worlds.

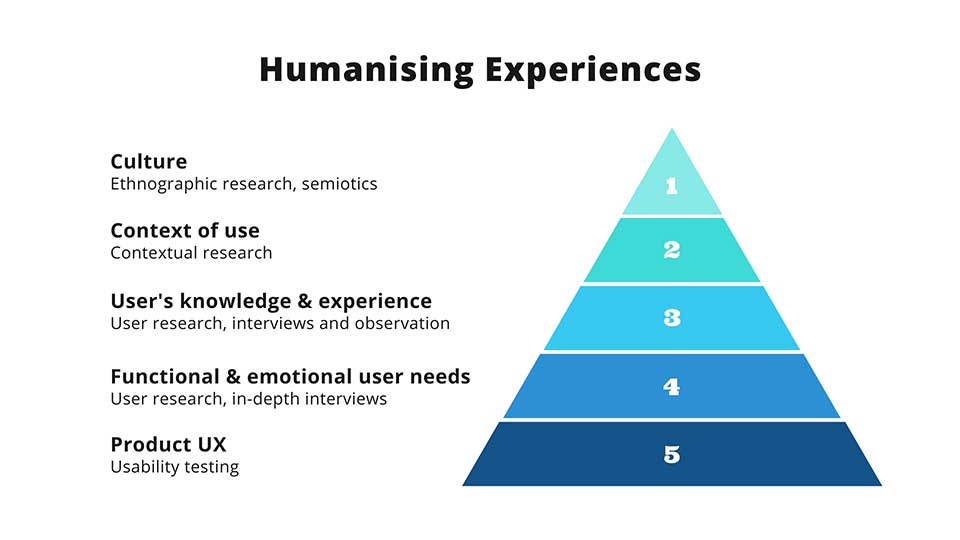

Our model for humanising experiences

Based on the described concepts and insights, we created a model for humanising experiences:

How can we bring the human perspective into customer and user experience? We analyse the culture, context, user behaviour and needs, and based on that, we create personas and journeys.

Conclusion

Culture and context shape users’ experiences, the stories their lives consist of, and therefore their expectations regarding products and brands. In researching users, context and culture, we uncover needs and emotions, enabling us to identify how a product or service can help meet these needs. We work with personas to illustrate your customers in their cultural context and with journeys to show how to guide users along their path by using messaging and cultural codes they understand to create humanised experiences. With the right signs and signals, we can show the users we have the right product for them. Speaking the users’ language on your website or in your marketing campaign will reach their heads and hearts.

Sabrina Duda, Head of UX, VERJ | A LAB Agency

Sabrina has over 20 years’ experience in UX. She joined VERJ, a LAB agency, as Head of User Experience in 2020 and is passionate about product development and delivering the best user experience aligned with business objectives.

Sabrina previously set up her own agency, eye square, in Berlin. Over the course of 12 years, she grew the company to 50 employees, delivering projects for clients in Europe, the US and Asia.

She currently runs the Research Challenge workshop along with Jen Romano and Rebecca Destello and also mentors young professionals. She earned a Master of Science degree in Psychology at Humboldt University in Berlin, specialising in Engineering Psychology and Cognitive Ergonomics.